By Stateline.org’s Anna Claire Vollers

Grove Hill Memorial Hospital in nearby Clarke County similarly ceased delivering infants in October 2023, nine months after Monroe County Hospital in rural South Alabama discontinued its labor and delivery department.

The majority of the state’s poorest counties are found in an agricultural region that includes both hospitals. For many people in the area, there isn’t even an emergency room close by.

Over the course of her 40-year career, Stacey Gilchrist, a nurse and administrator, has worked in Thomasville, a small town located roughly 20 minutes north of Grove Hill. Due to financial issues, Thomasville’s hospital completely closed in September of last year. Even after years without a labor and delivery unit, women in labor continued to arrive at Thomasville Regional’s emergency room when they knew they wouldn’t be able to get to the closest delivering hospital.

Shortly after the Thomasville hospital closed, Gilchrist told Stateline, “We had a number of close calls where people couldn’t even make it to Grove Hill when they were delivering there.” She told how, while staff waited for neonatal specialists to arrive by ambulance from a distant delivery hospital, Thomasville nurses struggled to preserve the lives of a mother and baby who had delivered early in their emergency room.

You would get goosebumps just looking at what they had to do. “The mother and baby survived, but they had to get creative,” she said.

The closest birthing hospital is now more than an hour’s journey away for many families.

Obstetric services are no longer provided by the majority of rural hospitals nationwide. According to a new report from the institute for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform, a national policy institute dedicated to resolving health care concerns through reorganizing insurance payments, over 100 rural hospitals have ceased delivering newborns since the end of 2020. Labor and delivery services are still available in less than 1,000 rural hospitals across the country.

“On average, two rural labor and delivery departments across the country close their doors each month,” said Harold Miller, president and CEO of the organization.

Miller informed Stateline that it was the ideal storm. Health insurance policies do not cover the cost of births, hospitals lack the resources to offset those losses because they are also losing money on other services, and the number of births is declining. In addition, everything is more expensive in rural areas.

The closures have been caused in part by low Medicaid reimbursement amounts, a lack of staff, and a decline in birth numbers. In response, some states have changed the way Medicaid funding are allocated, permitted the establishment of freestanding birth centers, or encouraged obstetricians from urban regions to operate satellite clinics in rural areas.

However, the losses are still occurring. According to the research, since the end of 2020, at least one rural labor and delivery unit has been eliminated in 36 states. Sixteen have suffered at least three losses. Twelve, or one-third of Indiana’s rural hospital labor and delivery units, have been lost.

Studies have shown that an increase in births in hospital emergency rooms is linked to the decline of hospital-based obstetric care in rural regions. In rural areas that lose hospital obstetric services, the percentage of women without proper prenatal care also rises.

Additionally, when a baby is born three weeks or more early after rural labor and delivery closures, researchers have observed a rise in preterm births. Premature babies are more likely to die and become disabled.

Hospital-based maternity care has been declining for decades.

Obstetrics has historically cost hospitals money. Maintaining a labor and delivery department is more expensive than the insurance money a hospital receives for delivering a baby. This is particularly true for rural hospitals, which generate less money than their metropolitan counterparts due to fewer births.

Because labor and delivery is a round-the-clock service, it is costly and complex for any hospital, Miller said.

A doctor who can do cesarean sections, nurses with obstetric training, and an anesthetist for labor pain management and C-sections are among the staff members who must constantly be on call or available in a labor and delivery facility.

Regardless of the number of births, there is a certain fixed fee that a hospital must pay to have all of that, Miller stated.

In most situations, hospitals are reimbursed per birth by insurers rather than being compensated for maintaining that reserve capacity. Hospitals use the money they make from more profitable services to offset their obstetrics losses.

The fixed expenditures may be affordable for a major metropolitan hospital that treats thousands of newborns annually. They are far more difficult to defend for smaller rural hospitals. To keep the doors open, some have been forced to abandon their obstetric services.

According to Miller, you cannot support a failing service if you are not making money from other offerings.

Additionally, staffing is a recurring issue.

The obstetric services at Harrison County Hospital in Corydon, Indiana, a small town on the Kentucky border, were discontinued in March after hospital administrators said they couldn’t find an obstetrician. With an average of 400 births annually, it was the county’s only birthing hospital.

Additionally, the majority of providers do not want to be on call all the time, which is an issue in rural areas where there may only be one or two obstetricians. Family doctors with obstetrical training serve as both general practitioners and obstetricians in many rural locations.

Related Articles

-

Guns kill more US children than other causes, but state policies can help, study finds

-

How to stay cool in the heat wave hitting parts of the US even without air conditioning

-

More employers adopting ICHRAs, giving workers money to buy their own health insurance

-

NFL widows struggled to care for ex-players with CTE. They say a new study minimizes their pain

-

Natural disasters may be shaping babies brains

According to the Indiana Capital Chronicle, some patients were already traveling more than 30 minutes for care before Harrison County Hospital halted its obstetrical services. Due to the shutdown, it can take fifty minutes to drive to a hospital that has a labor and delivery unit or to see prenatal care providers.

Because families are afraid to risk going into labor spontaneously and then having to endure a terrifying hour-long drive to the hospital, longer drive durations can be dangerous and lead to more scheduled inductions and C-sections.

Reduced labor and delivery units would put additional strain on rural ambulance systems, which are already overburdened.

Additionally, hospitals frequently provide as a central location for additional maternity-related services that support the health of both mothers and infants.

Katy Kozhimannil, a professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, whose research focuses in part on maternal health policy with a focus on rural communities, added, “We’ve seen in rural counties that have hospital-based OB care that you’re more likely to have other supportive things like maternal mental health support, postpartum groups, lactation support, access to doula care, and midwifery services.”

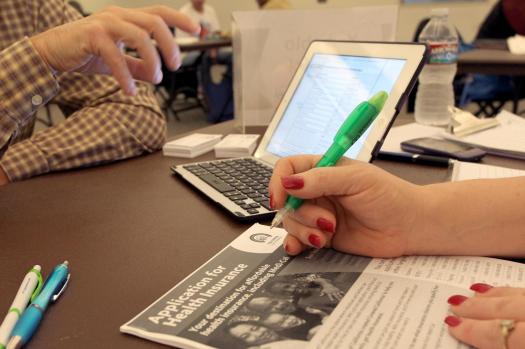

Nearly half of all newborns in rural locations around the US are covered by Medicaid, the state-federal public insurance program for low-income individuals. Additionally, women in small towns and rural areas are more likely than those in metropolitan areas to be covered by Medicaid.

According to experts, increasing Medicaid payments would be one method to save labor and delivery in many rural areas.

Congressional Republicans are debating which parts of Medicaid should be eliminated in order to help pay for the tax cuts under President Donald Trump’s tax and spending proposal. The provision of maternity services is not under threat.

However, states and hospitals will need to find ways to make up for any losses if Congress cuts federal funding for any parts of Medicaid. Some rural hospitals may no longer be able to afford labor and delivery services as a result of the knock-on effects, which could result in lower funding overall.

Cuts to Medicaid are going to be felt disproportionately in rural areas where Medicaid makes up a higher proportion of labor and delivery and for services in general, Kozhimannil said. Particularly for births, it is a very significant payer in remote hospitals.

Additionally, Miller thinks governments shouldn’t let commercial insurers off the hook for birth services, even though they frequently pay more than Medicaid.

The data shows that in many cases, commercial insurance plans operating in a state are not paying adequately for labor and delivery, Miller said. Hospitals will inform you that it’s commercial insurance as well as Medicaid.

He d like to see state insurance regulators pressure private insurance to pay more. In rural areas, private insurance covers more than 40% of births.

Yet there s no one magic bullet that will fix every rural hospital s bottom line, Miller said: For every hospital I ve talked to, it s been a different set of circumstances.

States Newsroom, 2025. Visit at stateline.org. Tribune Content Agency, LLC is the distributor.