The U.S. has hosted large numbers of foreign nationals before, including the wave of immigrants that crossed our border under President Biden’s watch.

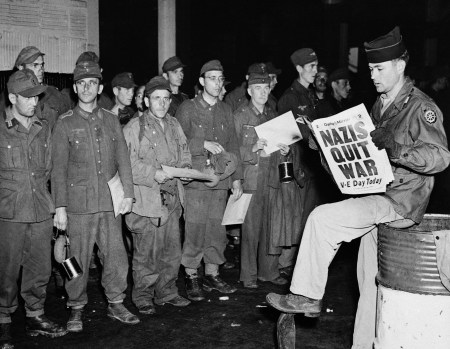

400,000 German soldiers settled in the United States during World War II. Because there was nowhere else to store them, these prisoners of war ended up here. With little room, food, or manpower to spare, Great Britain was living on the brink.

As a result, they spent their time imprisoned during the war in six hundred largely hurried and now-forgotten prisoner of war camps spread around the United States, from Massachusetts (Cape Cod, Ft. Devens) to California, with several camps created Texas, Georgia, and Arkansas.

With the exception of officials, the inmates supplied the nation with labor, partially substituting for young American men in the armed forces.

In Kansas, Iowa, North Carolina, and other places, the POWS maintained fields and herded animals. They were cowboys in Texas and forestry workers in New Hampshire and Maine.

The majority of the soldiers were not ardent Nazis, but many of the officers and noncoms were. However, the Nazis were frequently in charge of the inner operations of the camps and administered punishment, even murder.

Following the Allied defeat of General Erwin Rommel’s renowned Afrika Korps in North Africa in May 1943, the first group of captives arrived.

The allied triumph followed Operation Torch, the American invasion in November 1942. It was a precursor to Hitler’s Germany’s ultimate collapse, together with the Russian victory over the Germans at Stalingrad.

After the battle, over 170,000 German soldiers—among them 12 generals—were captured and sent to the United States for internment.

There would soon be thousands more coming to a nation that has not dealt with POWs since the Civil War.

Given that both Germany and the United States had ratified the Geneva Convention, the German prisoners were given favorable treatment in the hopes that American POWs detained in Japan and Germany would receive the same treatment. This was frequently not the case.

The comparatively low number of escape attempts was explained by the favorable treatment. America was too big, anyway.

There was only one German escapee who returned to Germany to continue the fight. After leaving a camp in Oklahoma, this tenacious German hitched a ride to Baltimore, negotiated his way onto a cargo headed for Lisbon, and traveled via Portugal and Italy to reach Germany. Later, before he could imagine starting a travel firm, he was captured.

William Geroux’s book The Fifteen, which explores murder, retaliation, and the forgotten story of Nazi prisoners of war in America, covers all of this and more.

The murder by fervent Nazis, hangings, and beating deaths of numerous more inmates who were alleged to have wavered in their support for Hitler and Nazism constituted the story’s dark side.

To beat and murder inmates who were deemed too friendly with American officials or who were suspected of being informers, the Nazis established covert squads in the camps.

In the end, the United States would detain and, after following the proper procedures, execute 15 ardent Nazis on murder charges. They were all given hanging sentences.

Hitler’s Third Reich imposed death sentences on 15 American POWs on false accusations of war crimes after learning about the sentencing from the Swiss.

President Harry Truman remitted the sentence of the fifteenth Nazi convicted to 20 years, while the other fourteen were hung.

Hitler shot himself, Nazi Germany fell, and Germany surrendered, saving the 15 Americans from execution.

They sent the inmates home. Nonetheless, some 5,000 of them moved back to the United States and established businesses, worked as doctors, lawyers, and artists.

Afrika Korps artilleryman Gerd Kruse once remarked, “I turned around as soon as I stepped foot on German soil and saw what happened.” He managed the family farm and married an American.

“You can do it here in America,” said Frieda Goedecke, who founded a manufacturing business and a retail store with her prisoner husband Heinrich. I don’t think you can do it anywhere else.

The email address of seasoned political writer Peter Lucas is [email protected].